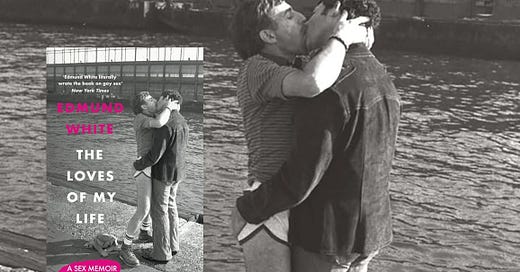

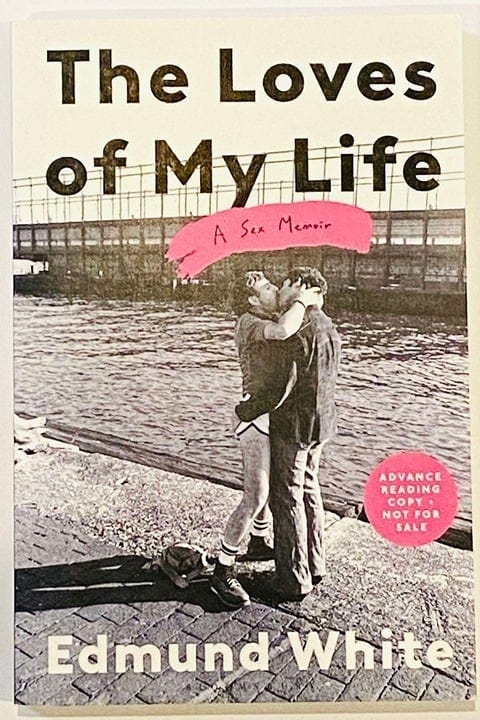

Read a Short Excerpt From Edmund White's 'The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir'

"For me, love was always passionate and one-sided, aspirational and impossible, never domestic and mutual," writes the 85-year-old “paterfamilias of queer literature."

The first book by Edmund White I read was his landmark 1982 semi-autobiographical novel, A Boy’s Own Story. Although it’s set in the 1950s, and I read it in the early ‘90s—more than a decade after the provocative book had been published—I was blown away by the frank descriptions of a young man’s longing and graphic explorations of gay sex. Since then, I’ve read a great many of his novels and nonfiction. But it’s his memoirs that keep me rapt.

When he was 65, he published My Lives, which detailed many of his past lovers and exploits. He followed that with City Boy, about his experiences in 1970s New York City. Now 85, White published The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir earlier this year and it’s just as eye-popping and explosive in its own special way as his previous books. As he explains up front: “I'm at an age when writers are supposed to say finally what mattered most to them—for me it would be thousands of sex partners.”

As Dan Kois wrote in Slate while reviewing the book, White "views his 70 years of sex with affection and a hint of nostalgic lust, but most of all with melancholy. I don’t know that I’ve ever read a book about sex that’s quite so self-effacing. I’m sure this must be the only book about having sex thousands of times to begin, 'Although I have a small penis …'”

While I agree that Ed includes a lot of explicit details about hookups, trysts and longtime lovers, I was particularly moved by a chapter titled “Jim” that details the "great love" of his life. It’s a heartbreaking story, but for fans of White’s work, he explains that his novel The Beautiful Room Is Empty is about Jim. As he also details in this memoir, while he was teaching at Brown in 1990, he got a letter from Jim’s lover who said that Jim had died of AIDS. “He said Jim had read my novel and been pleased by it. And that was that.”

Beyond that tidbit, I was also thrilled by this confession:

“Some people wonder why I’ve not written about them. If they’re a current part of my life, I need to keep them on life support; my husband is Michael Carroll, whom I’ve been with since 1995. I’ve never written about him; he’s too precious to me.”

I asked Bloomsbury, the publisher of The Loves of My Life, for permission to share an excerpt from a particularly revealing section of that chapter, which you can read below.

When I speak of the great love of my life, I don’t mean the degree to which someone loved me. I mean how madly, desperately I was in love. Once when I was sobbing in public over my broken heart over some man or another, Joyce Carol Oates, friend and colleague at Princeton, asked me coolly how many men had I rejected and hurt? Of course in my egotism I hadn’t kept track of that, though they must have been in the dozens. For me, love was always passionate and one-sided, aspirational and impossible, never domestic and mutual. Did I need that distance, that anguish, to contemplate the beloved and write about him? When Jim went crazy and ran up and down the psych ward convinced his arms were on fire, I kept wondering what I must have said. It was always about me, some lack or evil or mistake in me, my failure to be lovable. Now, in the cold polar heart of old age, I look at all my travails in love as comical and pointless, repetitious and dishonorable.

* * *

I used to be shocked when Virgil Thomson the composer—who wrote the opera Four Saints in Three Acts with Gertrude Stein, which received its premiere in 1934 with an all-black cast—used to be called to the telephone. I knew him in the 1970s when he was almost in his eighties; he’d come back to the table and say, “Well, Smitty is dead,” and just sit down and continue the conversation about something else. I was amazed that he could receive the news with such indifference about such a close friend.

Now that I’m in my eighties, I realize his emotion was stoicism, not indifference; someone who outlives his contemporaries knows that he very likely will be next but that for the moment “he controls the narrative,” as pundits say. When you get to be old, everyone consults you about the biographies of your famous contemporaries. You get the last word, at least until the dead person’s Complete Letters come out.

A life, a love. I always say that Jim Ruddy was the great love of my life. What does that mean now he’s just a faint neural scratch on my brain? It seems the hippocampus delegates short-term memories to various other neurons, where they are encoded forever. Does that mean an electrode stimulating the right neurons could make Jim, his conversation, his deep voice, his big curved penis, as real as it was fifty or sixty years ago, a hologram? The wondering way he’d greet any declaration with a tentative acceptance? His always saying “Is that right?” no matter how preposterous one’s remark had been.

Maybe I’ve forgotten him because I wrote about him; I’ve always thought that writing about someone is the kiss-off. Nabokov, in Speak, Memory, was apprehensive about writing about his nanny since he liked revisiting her in his thoughts and he knew once he’d committed her to print, he’d lose her. Some people wonder why I’ve not written about them. If they’re a current part of my life, I need to keep them on life support; my husband is Michael Carroll, whom I’ve been with since 1995. I’ve never written about him; he’s too precious to me. My recent fiction is less autobiography and more thought experiment. I assemble my monsters from stolen body parts (his nape, her stutter). Often I want to lead the reader to a better (more compassionate, more forgiving, bolder, more loving) world by picturing it as if it already existed; George Meredith called that process “moral sculpture.”

What did it feel like to be in love?

Constant suspense. Does he love me yet? More? Less? Is he getting bored?

I always fell in love with the wrong person. Proust advises that falling in love means falling in love with the wrong person.

In college, I used to slow dance with athletes at a party in someone’s living room; I liked to feel their hard-ons pressing into me, to feel their muscles under their cashmere sweaters, to smell the mixture of cigarettes and English Leather cologne. Maybe because I was already twenty-nine when Stonewall took place, I was never gay and proud. I coauthored The Joy of Gay Sex and encouraged everyone else to be self-accepting, but I never was.

Later I discovered that people had thought of me as “hot,” but at the time, when I actually was hot, I hated myself. My cock was too small, a trick told me my mouth stank of rot, there was always an inch of flab around my waist. I had my hair straightened for the surfer look, in France I had fat suctioned off my stomach by a surgeon, then I wore a leather corset for a month. I was always fighting my weight—doctors, speed, fasting for twenty days in a Swiss clinic. Cabbage soup for a week. Lunch and dinner. No carbs. The Atkins diet. The Scarsdale diet. The grapefruit diet. The gym-four-nights-a-week diet. The white-wine-and-steak diet.

I could never see the problems beautiful men had. To me they were gods who had nothing to complain of. I couldn’t see they were frustrated in their careers. Or that they were hooked on drugs. Or that they felt intimidated by me, of all people. Or that they were lonely or afraid. In the 1960s, a drag queen named Brandy Alexander said to me, “Oh, Ed White, you’re the universal ball.” A female literary agent told me, “We all wanted you back then.” I found out years later a killingly handsome and accomplished friend of mine had tried to make me his partner. When I, groggy and self-hating as usual, hadn’t picked up on his overtures, he’d ended up with someone else, a friend of mine, almost a double.

Did I always endure unreciprocated love because I could only love (and write about it) when I was rejected? Did my low self-esteem seek out rejection, as in I wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would accept me? Or does everyone hope to trade up to a newer, better lover? Not social climbers but amorous climbers?

Truly a fantastic book. I was honored to review it for Hippocampus Magazine in January.