Greg Bourke Fought for Marriage Equality. Now He Hopes the Next Generation Is Ready to Defend Our Rights

"The next generation needs to pick this up and run with it ... because there's a lot of work for all of us to do."

This June, we're coming up on the 10-year anniversary of Obergefell v Hodges, the landmark Supreme Court case that helped win federal marriage equality. Since then, President Biden signed the bipartisan Respect for Marriage Act in 2022. Yet, since Trump's win in November and after his inauguration in January, there’s been a growing sense that same-gender marriage is on the "chopping block." I'm not sure if this is a ploy by well-meaning nonprofits to stoke fear to raise funds, or because of the plans laid out in the Project 2025 playbook, or a surge in social media frenzy on the subject—but it seems to have had an effect.

For example, on Dec. 7, a venue in rural Richmond, Kentucky, offered a free "queer wedding pop-up" to couples who wanted to get married since they felt they needed to do it before Trump was sworn in. They performed 27 marriages that day, including one that was recently featured in the New York Times “Vows” section. (I interviewed people about this event and plan to publish something on it very soon.) We haven't seen this sort of mad dash to get hitched since California's Prop 8 ballot measure in 2008, although we live in a very different time.

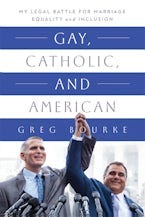

When I started looking at ways of covering arguably one of the most important Supreme Court cases of our lifetime—since it radically changed the idea of marriage in the United States—I realized Greg Bourke published a memoir about his activism and advocacy during the pandemic, and I’d missed it. He was one of the plaintiffs in the Obergefell case, and he also took on the Boy Scouts of America before that. In fact, I’d forgotten that I’d met Greg in 2013 when I was executive editor at Out magazine, and I’d organized a photo shoot with photographer Danielle Levitt that included him in a portrait alongside David Knapp and Pascal Tessier.

In his memoir, titled Gay, Catholic, and American, Greg writes about being at the party to celebrate the Out100 that year—which included Debbie Harry performing—and so many memories came flooding back. It was a time of optimism, when things seemed to be progressing toward inclusion and we had cautious hope. Then, in 2015, after the Supreme Court granted equal rights to more marginalized Americans, people felt like LGBTQ+ people were being seen as equals. Many people decided that the need for aggressive activism was over; they closed up nonprofits and turned their attention to other issues. When I asked Greg about that time, he shared his memories about another trailblazer (who I was also privileged to meet before she died in 2017), and who inspired so many of us at the time.

“Michael and I first met Edie Windsor at the Out100 Gala in 2013, where I was being recognized for my work advocating for queer inclusion in the Boy Scouts of America. Edie had already emerged as an icon of the marriage equality movement, and Michael and I had filed our July 2013 case in federal court challenging Kentucky’s marriage equality constitutional ban. We hit it off with Edie at the Out Gala and talked extensively.

“If Edie had not have been successful with her case, ours never would have been filed. Her success at SCOTUS was the absolute impetus we needed to see that marriage equality was not only possible through the court system, but genuinely attainable given the composition and sentiment of the U.S. Supreme Court when we filed.

“Having communication with Edie during the two years our case moved through the court system absolutely served as a source of great hope to the Kentucky Obergefell plaintiffs. She was really rooting us on, and told me so frequently. That encouragement I passed on to the other Kentucky plaintiffs, and we all celebrated having that type of endorsement from the person responsible for the most substantial decision related to marriage equality to that point. I personally found great comfort and strength in communications with Edie, and that was I kept the conversation going, and she was more than happy to keep the encouragement coming in return.”

I interviewed Greg in February, a month after Trump’s second inauguration, before Pope Francis died and conclave was formed to pick a new pope. The piece ran in The Revealer earlier this month, which you can read here. Below, you can find a longer version that includes more details about Greg’s marriage to his husband Michael (the two have been together for 43 years and were married legally in Canada in 2004 so have 21 years of legal marriage recognition), raising his kids in Louisville, Kentucky, and why he remains faithful to the Catholic church despite its many failings.

In particular, I was glad to hear that Greg remains sanguine, and he hopes that the younger generations will pick up the baton and continue fighting for equal rights.

“Michael and I make ourselves available all the time to be visible to advocate,” Greg told me. “We stay engaged; we think the fight is important. But we also acknowledge that it needs to be multigenerational. I think that would be beneficial for all of us: If we did more things in a multigenerational way. So we respect young people, and they respect us and everybody in-between. I think there's a whole lot more that we agree on than we disagree on, so let's figure out what we agree on and work to move those things forward. Because there's a lot of work for all of us to do.”

Read a version of this Q&A in The Revealer magazine.

Jerry Portwood: You finished your book during the pandemic, and you published it at the five-year anniversary of the Obergefell decision. What compelled you to write it?

Greg Bourke: I had a bit of an awakening, or a calling, that occurred while I was at church. It just kind of compelled me to take a look at what had been going on and transpiring in my life and to really reflect, analyze, and then record it. I felt like I had my hands in a lot of different things that were really important developments in the arc of gay history. I needed to record some of it because I think that a lot of that wouldn't have been available to people. A lot of that history has just been lost.

Another thing that I think is important is, you know, Michael and I, when we got together in 1982 in Kentucky, the world was a very different place, the odds were very much stacked against us. I think it's important to capture for people what the world was like when we made that commitment to each other, and how remarkable it is that we're still together today in 2025. We were the exception.

When we first got together, we didn't know any other gay couples. We knew gay people, but we didn't know gay couples who were trying to stay together and put a life together. It was uncharted territory for us, in our part of the country. It was a lot for us to try to take on. So I think it's still important that the book captures those early days and what it was like and then follows the progression of this very unlikely couple that turns into a family and then actually gets involved in some of these historic things that have happened to move the LGBTQ community forward in a couple of different perspectives.

It definitely feels like an important historical archive—especially because it explains how, when people are doing advocacy or activism, how many logistics go into it.

Absolutely. I really don't think people appreciate that. We didn't have a lot of downtime during those years. If you have a family, where you have both parents are working full-time corporate jobs that are very demanding, and you've got children in high school, and you're trying to you help 'em, support 'em, and get ‘em moving in the right direction, it takes a tremendous amount of time to just to keep up with those two things. So if you add on trying to take on the Boy Scouts of America and then take on the federal court system—it was pretty overwhelming at times. But we lived to tell the tale and, through all that, Michael and I are still together as a couple, and I think we're probably happier now than we ever have been in our lives.

People don't always remember that you were among many other plaintiffs in this case because Jim Obergefell was the named plaintiff. Can you explain how that happened and what it’s like for his name being the one front center?

Our case in Kentucky was Bourke v. Beshear. When the unfavorable ruling [came down at the Sixth Circuit] all four of the states decided independently that they thought it was best if they appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, so were given a very brief window of time to file those appeals. There was a mad scramble … we were all trying to see who was gonna get there first to the Supreme Court.

Obergefell v Hodges filed first. [Our lawyers] filed six minutes later. So, if a couple things went different ways, that case could have been named Bourke v Beshear. I'll tell you what I've told Jim Obergefell many times: I was glad that it was his name on the case instead of mine. First, I didn't have the time or the desire to be the name on that case. When we filed it, in 2014, I was still working. I didn't have the time to devote to what was required, what Jim kind of got sucked up into... Not only the name of the case but also the face of the case.

I'm sure there are a lot of great advantages and perks to it, but I'm glad it was him instead of me. And I still feel that way. From my perspective, it's been difficult at times; Michael and I have had to endure a lot of pushback, a lot of criticism, there were just a lot of things that happened over the years. So I’m really grateful that it was not my name that was on that case.

I know it can be quite difficult being Catholic in the Deep South since it’s considered this strange thing. Can you talk about Kentucky and how it’s different and whether you ever felt othered growing up Catholic, as well as realizing you were gay at a young age.

Speaking about Catholicism in general, I am an Irish American, my great-grandfather came from Ireland, so I grew up in this big Irish Catholic family. Every weekend, we would go and have dinner at my grandparents' houses, hang out with my cousins; every weekend we had a family reunion! Everybody was Catholic. And I went to Catholic school, right? So my whole world revolved around this Catholic community in Louisville. So let me talk about Louisville, I think we have more Catholics than we do Baptists or Presbyterians so there's a huge population of Catholics here.

If you look at the river cities along the Ohio River—Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, then Louisville—that's where the Irish float to when they came into America, so this community in Louisville, Kentucky is very, very Catholic. The Catholic schools here are the best schools in the city, a lot of non-Catholics actually go there because they have such great reputations.

So that was the world that I grew up in, and I really didn't feel othered; I kind of felt more like I was in the majority. In that respect, I was comfortable and happy with that—just because I got so much good reinforcement from my family, from my friends, who I am still in contact with.

Issues around masculinity are swirling, and you’ve been involved in organizations that deal with a version of masculinity. When JD Vance says something like, “We're gonna get the normal gay guy’s vote” or the “acceptable gay,” what’s your reaction to that?

I don't know what he'd consider a "normal gay" anyway. Because I don't know who he knows or who he doesn't know. But I just thought that was out of line. I don't think there's a thing as "normal gays"—there's just gays! I mean, we're a broad range; there's a spectrum. You've got the boring ones—like Michael and me—who are perfectly satisfied to wrap our lives together and live 'em for 43 years and just deal with whatever comes up. Then, you have other people who have a variety of different lifestyles and attitudes and things that they are seeking out of life, and I respect them all.

Your mission was to have a family, then you took on these powerful institutions. What kept you going through all of this? Because it seemed like a helluva lot of work!

I think a lot of that drive comes from my background and my family. My siblings—I have three brothers—they've all been extremely successful in their lives. We came from a family where that was kind of expected. We grew up in a Catholic community that expected you to excel. We went to very challenging schools that compelled us to not only achieve academically but also to be of service to our fellow man, to be faithful stewards as best we can.

My faith has driven so much of what I have done in life. The fact that I wanted to get involved in sustaining a relationship over a long period of time—like my parents who were married for 67 years when my father passed—I wanted to have that relationship. I wanted to have a family at some point. I don't think either of those things are outrageous asks. There are so many millions of Americans who seek and achieve the same thing. It's only when you start adding on some of the other things that came to me later in life.

Now, as an openly gay man—I've been out since I was 19 years old, and I'm 67 now—I never really had to deal with discrimination. Nothing that I couldn't handle, nothing that really motivated me to get extremely active until I got ousted from my position as a Scoutmaster. When they said I was not competent to do a job that I'd been doing for 10 years. That was the last straw. Prior to that, I was just so fortunate in terms of being able to be openly gay at my place of work; I was able to be myself and it was not a problem. I never got turned away from a school, or a job, or any kind of a social group because I was openly gay. It was only when the Boy Scouts said, “You have to leave,” that I knew how wrong that was. I knew that was happening with other people, but it wasn't happening to me.

I think it's what many people have to experience: You have to have that personal experience of discrimination to really get motivated. Now, I appreciate all the people—and there are plenty of folks—who get out there and get active just because it's the right thing to do. But for the first big majority of my life, you know, what was important to me was having a job, having a relationship, having a family. And that was a lot to do as a gay man. So I didn't really feel like I had a whole lot left to do, to give, in addition to that in other areas until something happened to me. Then it was like, “OK, I have to do something about this. And what can I do?” Then some opportunities presented themselves to me, and I acted on it.

I think many people's reaction would be anger. Instead, you said, “I love the Boy Scouts and I wanna change it.” The same with the Church. Some people would say, “The Church rejects me, I'm gonna reject the Church back.” You didn't, you don't, exhibit that sort of animus. Instead it seems like you decide: I love this thing, and I'm gonna make it better.

Well, I wish more people would do that. Yes, you're right. Sometimes the easier thing to do is just to pack your bags, shake the dust off your feet and walk away and say, “I'm not welcome here; I'm leaving.” I never really felt that. I've never had a break with the Catholic Church. I've never had that moment where I said, “I can't go back, or they don't want me to come back.” So I've been able to sustain that over a period of my whole lifetime. And it's so important that I had that continuity in my life to be able to just have it going and going and going. I get frustrated with the Church but never to the point where I get really angry or want to leave.

To get back to your question, I think it's harder to stay and try to fight things and make things better. But as I have seen personally, if you stay, then people have to continue to deal with you. You know, then the opposition is gone.

As my husband says all the time: “If we leave, they win.” If everybody just walks away, then the bullies are gonna win, the injustice is gonna remain, and nothing’s gonna get changed. But if you stay, and you're reasonable and you explain why you should be included, why this shouldn't have happened, why it should change, you know, people kinda have to listen to you. I mean they can tune you out to a certain extent, but if you get enough people together—and you're putting the messages out there in the right way—they have to acknowledge that and deal with it.

Well, there's the “big C” Church and then there's the lowercase church. I know the Catholic laity is quite different and can be quite progressive compared to the power structure of the Church with the big C. Is that how it is for you?

Yeah, the big Church just can't seem to figure the whole situation out with LGBTQ people, especially under our current Pope [Francis]. It seems to shift by week, by month. So we never quite know what we're dealing with. In the archdiocese of Louisville, there seems to be a significant progressive wing, and we have some that are very conservative ones. You can walk into one parish in this archdiocese and potentially hear a sermon you know that's railing against gay people, and then go in another parish where they are welcome and celebrated and included. There's just so much variety even within even one single archdiocese, and I think most archdiocese across the country are similar to Louisville. You have a broad range of parishes and options that are available to people. If you can find one, then you can be comfortable and happy in that environment.

Michael and I joined our parish, Our Lady of Lourdes, out of convenience because it's a block-and-a-half from the house that we bought. We didn't know what to expect, you know, if it was welcoming, how they would feel. Very early on in that relationship—and we've been at that parish for 37 years now, so a long time—I went in and had a meeting with our pastor. At that point, I explained to him that Michael and I were gay, and I wanted to make sure that we were welcome. He assured me that we were absolutely welcome, and we've been fine ever since. So after we got that kind of approval from our local parish—so the “small c” church—we got involved in a variety of different activities.

You even became a Communion minister, correct?

Yeah I still am. I've been a communion minister at Lourdes for 25 years. And more recently, I've been involved as a sacristan, which is a pretty demanding role at the church. We have a long relationship with our parish, including the fact that our two children, who are now adults, both went to the parish schools. Our roots are so deep there, I can't imagine ever not being a member of that parish. But as is often the case, pastors set the tone, and every six to 12 years, you get a new pastor, so you never know what you're gonna get when the pastor rotation comes up. That's at the discretion of the archbishop of Louisville, so we have some potential folks that could be assigned here that would change the climate of the parish overnight. That hasn't happened yet, but it could.

Back to Pope Francis and the confusion. At one point, he appears inclusive toward LGBTQ people—now gay people can be baptized and you can be a godparent—then you get other negative comments about “gender ideology” and trans people. How does it affect you?

I'm coming from that progressive wing of the Catholic church, and I'm confused by it. I think people on the more conservative side of the Catholic church are just as confused, just as frustrated. So I have some sympathy for them. We're all in the same place: He has not had a consistent message; he's reversed course a couple of times; he's been caught using gay slurs. It's frustrating, and I think the whole church would like more clarity.

We recently, at the Pope's direction, went through this Synod project for a couple years where we listened to people at a very grassroots level, and it was all supposed to flow up. There was optimism that there would be some great changes that came out of that, whether it was going to be women deacons or better inclusion of LGBTQ people. And practically none of it happened. It was significant though that, at least, the effort was made to try to listen to people. Some of the voices got heard, so I think that was important, but really nothing's changed.

That's what's frustrating to me: that we have a Pope who is so often criticized for being too progressive, and too “soft on gays,” and all this, and from my perspective, things haven't really changed that much. I don't know what people are complaining about; Church doctrine has not changed. So yeah, I get frustrated with the Church, but I also know, it's my home. And I don't know who I would be without my experience in the Church. It's been so integral to my whole life—from baptism to right now. I've always been active in the church.

It's the same way, I can't envision not being an American. I know people who expatriate and retire and move to other places. But I can't imagine not being an American. It's the same way with Catholicism for me: I was born that way, it's been my whole life, my family, my friends... It's like, that's what makes me who I am, so I can't really envision not being Catholic. So everything that’s happening with the Pope and the Catholic church and how uncomfortable it is and how it has a problem with equality and inclusion. Yeah, it's got all that! But it's still my church, the same way that this is still my country—with all its flaws. And I don't like what's going on with the country, but I'm not gonna disown my country, and I'm not gonna disown my Church. They're just too important to me, so I will take those to the grave with me and do it gladly.

Speaking of, you also included a recent battle to get your joint tombstones into a Catholic cemetery. Anybody who hasn't read about that will be surprised. I mean, you even seem surprised by it!

I didn't realize we were gonna get that much pushback. Michael and I were planning to do this anyway; we wanna get buried in the Catholic cemetery. We didn't realize this was gonna turn into, like, a nine-month process of getting the archdiocese to approve our tombstone. It was unexpected. It was frustrating; it was everything.

I got a little angry over that, but it was a situation where it was good news, bad news. We kind of took the archdiocese on, and they said, “OK, we're not gonna give you everything you want. We're gonna allow you two to be buried together, in a Catholic cemetery, so we'll allow you to have a joint headstone. But, we will not allow you to have certain elements on that headstone.”

They told us we could not have the image of interlocking rings. When you walk through a Catholic cemetery here, you will see the vast majority of married couples who were married together have this imagery. We were told we couldn't have that. We also wanted to have another image, that of the Supreme Court, engraved on the headstone, which I understand was probably more controversial. But again, if you walk through the same cemetery, you just go a couple rows away from where we are, and you see images of Churchill Downs; you see images of people fishing; the Kentucky Wildcat logo. I mean, just really strange and unusual things. But the Archdiocese of Louisville thought it was just a bridge too far to allow us to have an image of the Supreme Court on our tombstone. So we lost a couple things, but I think we won more.

This was a very public battle. We had the local media covering this thing, and the archdiocese was really forced to make a decision, and it set a precedent: Yes, two same-sex people can be buried together, in a grave like this, we just can't have the interlocking rings. So, you know, we got most of what we wanted, and we think it was an important fight that we took that on.

All I kept thinking was "yet." Because you probably have another 30 or more years—so who knows what's gonna happen in that time!

I don't know about that. I hope you're right, but I don't know.

You wrote about feeling you had a connection with Justice Sotomayor, who’s the progressive Catholic on the Court—which has gotten more Catholic and more conservative since your case was heard. What does it mean to you that the six of the nine Supreme Court justices are Catholic and that it’s grown more conservative since your experience?

It doesn't bother me that it's so Catholic, but it does bother me that it's so conservative Catholic. Because the three that were appointed by President Trump really shifted the nature of the court. You could have found some progressive Catholics, believe me, there are lots of them out there. The decision was made to bring in conservative Catholics and those are the ones who are willing to die on this one issue. They were brought in, in my opinion, specifically to target Roe v. Wade and, in fact, they did. I'm not sure what will happen beyond that. I think it's possible that they could pivot and target Obergefell. It hasn't happened yet, but it could.

I know it takes a while, and I haven't seen any serious, significant challenges at the District Court level yet. There have been some filings that have been made; most of them get dismissed. I just worry about it, like a lot of people.

For many years, as these conservative justices were added to the court, people would come to me and ask, “Are you concerned what they might do with Obergefell? Are you concerned with what they might do with Roe v. Wade?” My response was always: “That is settled. I'm not worried about it. Listen to what they said in their testimony when they were being vetted in the Senate. That's finished law, and we're not gonna revisit that. They don't overturn stuff like that!"

Then what happened?

So now I have an ultra-cautious approach, and I feel like it could happen; it might happen. Now, we have the Respect for Marriage Act, and I think that's great. We were there when it was signed. I thought that was fabulous! I think it's a very good protection. But I think what a lot of Americans are starting to feel is: Anything that's been done in the past, can get undone very very quickly these days—if people don't stand up and fight for it and try to stop it from happening. You know, I’m willing to do my part, but there's going to have to be a whole lot of other people who stand up, too. I think they're out there. I mean, marriage equality has never been more popular in America. Right? So everybody wants it, so my question is: Who doesn’t want it? There seems to be a very, very small segment of our population, and some of them are Catholic, some of them are Baptist, but it's a small percentage.

I don't know if it's 15 or 25 percent, but we can't let [that small] percent of our population determine policy and laws that are going to affect the vast majority of us who want something different. Who want things like marriage equality protected in our country, in our constitution.

You also talk about this idea of “changing hearts and minds,” which I think is really great because it reminded me that this is a euphemism for how the minority must try to change the ideas of the majority, which in fact is why we have democracy. Because the majority isn't supposed to crush the minority, and it isn't actually the minority's job to change hearts and minds—it's the job of a representational democracy to protect everyone. So I really appreciated that you wrote about how you got very frustrated with people saying, “We have to wait until you change hearts and minds before we can get this form of equality.”

I felt like we had been waiting long enough. And if it was simple, it would have happened more rapidly than it did. In Kentucky, if we were waiting for “hearts and minds” to change, we would probably have to get 95-percent of Kentuckians to really feel strongly about marriage equality before we could get something through our legislature here.

There's so much resistance so, at a certain point, you realize some people's hearts are so rotten you can't change 'em and you know and their minds are so bad, they're unwilling to listen to arguments for reason or to think empathetically, it's you just can't reach some people and I'm not saying it's a majority, it's a small number of people who are willing to dig in and do whatever they can or whatever they have to to to keep from from having to having to change or think about change.

Well, change is scary.

Right, and the change part is what people are resistant to some people don't want to change. They learned something when they were very young, they learned something about gay people, maybe they learned it in church, maybe they got it from the family or both places, and it's really hard to change the way they think, the way they feel, and what they believe when they got it so early in life and they got it time and time again and it's been reinforced for so long.We have some Kentuckians here who are never gonna change the way the feel about things, our only hope is the next generation that comes up after them is gonna be a little more open and I think that's proving to be the case.