Notes on Love and Life: Our Success Story—Despite the Odds

Domestic tranquility (sorta) and how our professional careers shaped our lives.

This is the third part in a four-part series of essays by Howard N. Fox.

Next Up»

Go back and read the first essay:

The second essay

About the same time that I applied for, and was hired, as a temporary research assistant for a major exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, it soon became—much to my hope and future evolution—a permanent position. I had no formal training in art or art history, and never had planned to or even dreamed of working in a museum. Yet, here I was, a punky graduate student plucked from academia and on the curatorial staff of a still-new modern art museum on the National Mall, flanked by the U.S. Capitol, the Washington Monument, and the Lincoln Memorial. Whodathunkit!?!

I started in 1975, and my Hirshhorn years—which lasted until 1985—were exhilarating. After fulfilling typical research assignments on a major exhibition, which celebrated a century contributions of immigrant artists to the United States, and was timed to coincide with America’s Bicentennial in 1976, I was appointed to a junior level project organizing a thematic exhibition focused on the “animal in art.” It was my job to select it entirely from the museum’s permanent collection and to author its slender catalogue—my first museum publication. Having demonstrated my chops as a cub curator, museum director Abram Lerner asked if I would be interested in organizing the Hirshhorn’s first major exhibition of contemporary, cutting-edge art, with the aim of staking the museum’s place “on the map” together with the other major contemporary art museums in North America.

I nearly wet my pants when Mr. Lerner made the offer. I cleared my throat and replied, “Well, I’ll think about it.” He thanked me and escorted me to his office door. As if performing a punchline out of a Hollywood comedy, I turned to him and eagerly declared: “Yes!”

That show became seminal in my early museum career. As it happened, the survey exhibition, which became the inaugural in an annual series titled Directions, roughly coincided with New York City’s Whitney Museum’s Biennial, a wide-angle snapshot presented as a grab-bag of very recent art nationally, but habitually trained on New York artists represented by one or two works each. Directions, by contrast, was organized thematically, focusing on only 18 artists, each represented with multiple works and accompanying catalogue essays. The Village Voice, New York City’s vaunted lefty-liberal alternative newsweekly ran a two-page spread reviewing both exhibitions. The headline, spanning both pages, read: “Whitney Museum No / Hirshhorn Museum Yes.” Seeing that, I nearly creamed in my jeans. That was an “orgasm” to remember!

After a while, it all seemed to be a chore, even if a pleasant one. Douglas’ and my main purpose in life together was to continue to pursue our ideals and cherish that we had our ideals. Literature and art. Douglas and Howard. Friends and associates. Work and more work. We never, ever, thought of ourselves as the privileged scions of rich folks with connections. We simply weren’t. We were both middle-class kids who attended public schools and public universities. We loved our work, and we worked for what we loved. By inexplicable chance, we were able to continue to do what we loved doing. Neither of us ever earned a lot of money, but we always had each other and encouraged and supported each other’s creativity and dedication to our pursuits and to our relationship.

In Washington, we were perceived as the young men about town. We attended a White House reception—openly as a couple—for American poets and met President Carter and Mrs. Carter. We were invited to a sit-down dinner—as a couple—at Vice President Mondale’s official residence. We attended numerous embassy parties and private dinners and museum receptions all around town. We were received and accepted as a gay couple in the nation’s capital at a time when homosexuality was still a crime in the majority of the United States. Lucky us! But after a decade at the Hirshhorn Museum, I began to realize that either I would spend the rest of my career there, or that it was time to move on.

I’d been to Los Angeles several times over my decade at the Hirshhorn, and in fact probably spent more time in Los Angeles on my 10- and 12-day trips there than I did in my many brief trips to New York, a quick train ride away from D.C. I recall calling Douglas on the first day or my first trip to L.A., in 1979, and reporting that it was one of the most repellent and simultaneously alluring places I’d ever seen. Returning home almost two weeks later, I mused that I felt that our destiny might be linked up with the City of Angels.

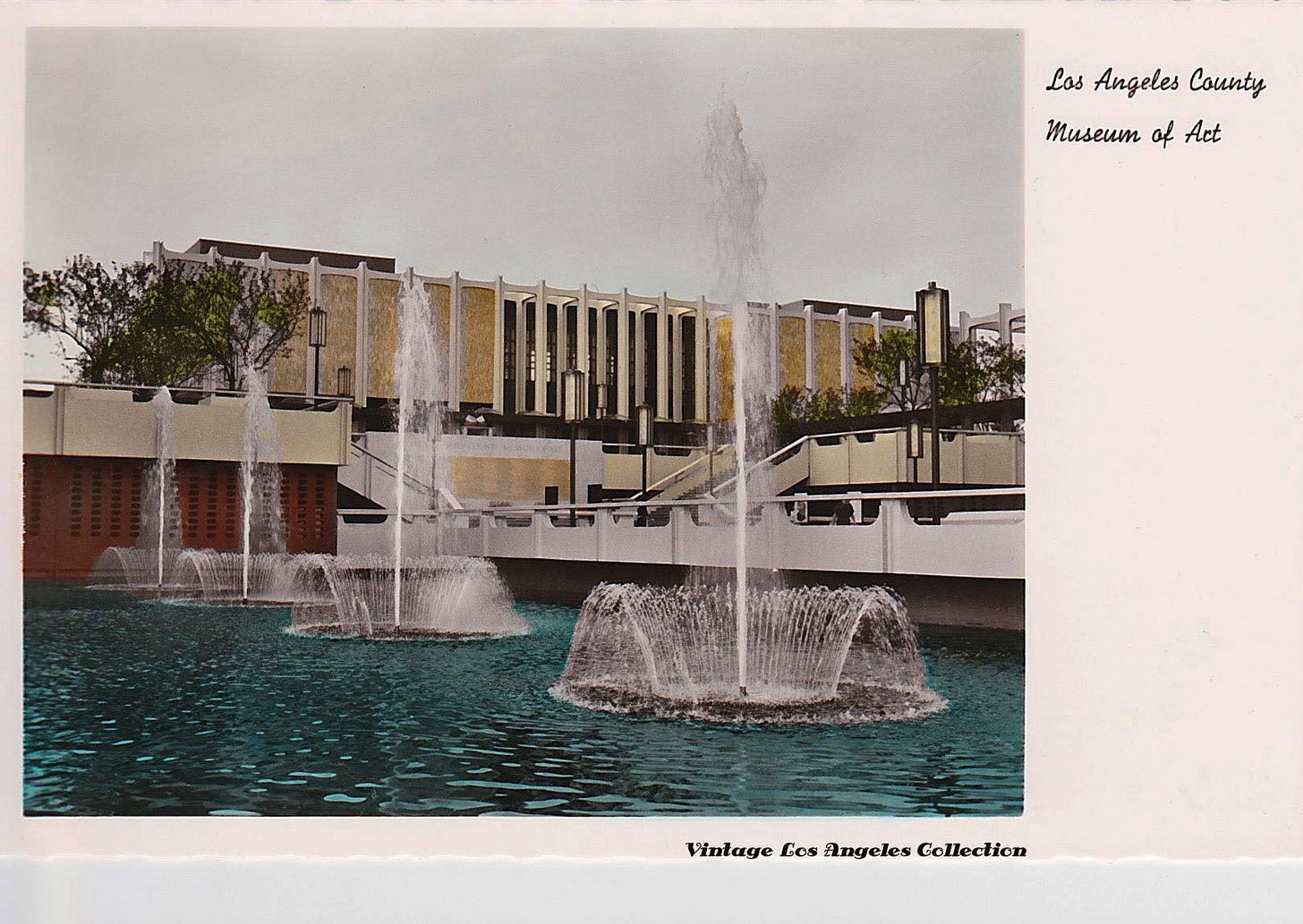

One day in 1985, I received a totally unanticipated phone call from Earl A. Powell III (more familiarly known to everybody as Rusty), then director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Rusty (whom I’d never met, even when he was a curator at the neighboring National Gallery of Art) was telephoning me at the office to say that he’d like to invite me to Los Angeles to interview me for the position of curator of contemporary art at LACMA. My office mate, Phyllis, could not help but overhear my end of the conversation. Upon hanging up the phone after that polite yet enticing offer, she asked me, almost breathlessly, “Howard, what was that about?” After a slight pause to catch my own breath, I responded “Phyllis, I think that was destiny calling.”

It turned out to be true. In June of 1985, Douglas and I and our cat Kiwi flew to Los Angeles and found a truly lovely unit for rent in a nearly new condominium building directly across Wilshire Boulevard from LACMA’s main entrance. Douglas found a small but adequate office—his first time running his press outside of a spare bedroom—just a couple of blocks away. All our belongings, and his full inventory of books, arrived a day or two after we did. Suddenly, we were living like grown-ups in a vast new city that seemed unruly, brash, and venturesome in dimensions that so contrasted with the universities and the federal museum where we’d spent our early professional lives together.

As I’d perceived from my several previous visits, I knew that L.A. was quickly, and solidly, emerging as an international focal point for contemporary art. Plus, the literary world there was burgeoning, too. We were in a right place at the right time. We didn’t plan or even foresee any of this; we didn’t have family or professional connections or an “old boy” network of cronies, or rich folks, or any other “white privilege” to get us there. It just sort of ensued from the work we’d been doing all along. We were exceedingly fortunate, and we knew it.

Our first year in Los Angeles we were drowning—almost gagging—on the nightly receptions, gallery openings, visits to art collectors, and dinners at many very nice restaurants that my new and very visible position at the city’s largest museum proffered to us. After a while, it felt more like an exhausting imposition on our life, but we engaged it with good cheer, conviviality, and grace, even on the nights when we wished we could just stay home and watch TV and share a big bowl of freshly popped corn. For all the glitz of which we were basically obligated to partake, we were two pretty regular guys who happened to enjoy luck and good fortune.

One of the most memorable and endearing moments of this year-long hurly-burly was when an aged, semi-closeted gay man from another generation came up to me after my festive cocktail-party-with-heavy-hors-d’oeuvres introduction to LACMA’s Modern and Contemporary Art Council (whose annual dues provided the 20th-century art department’s only sustained source of income for art acquisitions) and declared how thankful he was for my “important and courageous” for me to introduce Douglas as my life partner to the full group. I guess I thought it was important, but not especially courageous. Times had changed.

We also enjoyed total acceptance as a gay couple, even among the many straight folks who invited us into their homes. We can’t guess what people may have said about us behind our backs, but we never encountered or sensed any discrimination, disdain, or discomfort with who, and “what,” we are: a couple of friendly, well-spoken, good-humored queers. They liked us, and we liked them, many of whom befriended us and we them. Over time I’d been invited to speak at memorial services for several of them. In today’s Trumpian epoch we may have to assert our LGBTQ+ rights as human beings who don’t fit Mr. Trump’s declaration that there are “only two genders: male and female.” Genitals, and what they mean to you, do not compulsorily dictate your behavior or identity: Get wise, Mr. President.

In my 24 years at LACMA I’ve documented approximately 1,500 studio visits I’ve done with artists as internationally renowned as Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, proudly out and gay David Hockney, as well as many, many mid-career notables, emerging artists, and even graduate students. I wasn’t just running with the blue-chip guys. I made it a point to explore, support, and acquire the work of and exhibit younger artists (some of whom, I’ll frankly acknowledge I’ve never heard of again). As a curator of contemporary art, I assert the right to be wrong; museum curators of contemporary art ought not present themselves as gatekeepers and arbiters of what is “worthy.” They should seek out and explain to the best of their insights to as wide an audience as their institutions enable them, why artists are doing what they are doing. And I had ample opportunity to do that, both in and out of the museum.

Once, and only once, we encountered Christopher Isherwood and his partner Don Bachardy. Douglas had his camera with him and asked Isherwood, “May I take your picture? ‘I Am a Camera.’” Isherwood was displeased and scornful and turned away. No pic, only an awkward, if fondly intended, memory.

I can’t claim that any museum could adequately represent the feverish, chaotic, and overwhelmingly robust activity of the free-for-all of global contemporary art. I confess that I don’t believe I helped build anything like a “definitive” museum collection of contemporary art—for even such a notion is a chimera, a pipe dream. I saw my forte primarily as an exhibitions-oriented curator. And I’ve always insisted on writing catalogues, online essays, pamphlets, and even gallery wall texts as an essential responsibility of my job for any exhibition I’ve ever been involved in, at LACMA or elsewhere. After all, exhibitions come and go; catalogues exist forever and ever (even if they only sit unopened on library shelves).

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles Douglas' press published a virtual pantheon of innovative American writers including such luminaries, recognizable to readers of serious contemporary literature, as Fanny Howe, Steve Katz, Russell Banks, Raymond Federman, Lyn Hejinan, Charles Bernstein, and playwright and Mac Wellman. Douglas also focused on major world translations by figures such as Knut Hamsun, Adonis, Andre Breton, Rene Crevel, and Jacques Rouboud—just a few of the hundreds of books he published in translation, for which the press was awarded both the American Literary Translation Award for his dedication to translation and, and later Douglas was awarded the prestigious "Officier de L'Ordre des arts et des lettres" by the French government.

After the French cultural attaché in Los Angels opened the velvet box to award Douglas with his medal, he confided: “I thought you were being awarded a knighthood, but I see you’re even higher; you’re an officier! If I were an Englishman, I suppose I’d have to kneel.” In any case, Douglas displayed his medal only once, at a small New Year’s Eve party at our condo a couple of weeks ago.

Over Sun & Moon Press’ long run, Douglas was invited to and attended major conferences in Brazil, Antwerp, Amsterdam, Seoul, Paris, and elsewhere, often to read his own poetry. Recently Douglas was honored at the annual fundraising gala of Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center, Southern California’s oldest literary foundation, with a Distinguished Service Award for “his inspiring and generous service to the literary community.” As far as I can tell, Douglas has reached far more readers through his publications and several blogs (five of them!) than I ever did through my publications, and I’ve had some pretty prestigious publishers. C’est la vie. Fact remains, we’ve both lucked out (with some persistence and real elbow grease) the exceptional good fortune to pursue the vision and ideals that we’ve both aspired to.

Running a non-profit press entailed beleaguering bureaucracy. Applying for grants, documenting every plan and book published, reporting detailed income and expenditure was like reporting your tax—except the process for a non-profit is exceedingly complex and must be executed several times a year. Douglas decided to relinquish Sun & Moon Press’ non-profit status and rebrand its work under the rubric Green Integer Press. I forget precisely why he chose this title, but it has come to identify his distinctive vision as a publisher through his many books that have earned the press’s following. Although it’s not, by definition, a non-profit organization, it’s scarcely a profitable enterprise. Nor is it a hobby: He and his managing editor Pablo Capra take in several thousands of dollars per year, and the press just squeaks by. But Green Integer press is a viable business that has endured since 1997 and will continue as long as he and Pablo can make it happen. That’s an American Dream!

In the early ‘90s at the annual Frankfurt Book Fair—the largest and most prestigious international expo in the global publishing industry—one of Random House’s topmost execs sought out Douglas at his tiny display booth and told him that he envied what Douglas had been able to do with his nimble and not-for-profit-oriented press. That was a remarkable compliment that only served Douglas’ aspirations to do what the major publishers essentially restrained themselves from doing, in the way that the big movie studios generally fob off the most serious and artistically venturesome to the indies. As if to prove his admiration correct, Penguin Books (which later merged with Random House) bought the paperback rights to Sun & Mon Press’ hardback first edition of Paul Auster’s extraordinarily acclaimed New York Trilogy, which subsequently became a best seller on the commercial publishing market. The modest percentage of royalties that Sun & Moon Press received substantially supported its activities for several years.

Douglas has never wavered from his self-appointed mission (though he’s frequently lamented that his press has often depended on life support from our combined modest income) and as a poet and film historian. He has recently completed the first of a multi-volume history titled My Queer Cinema: LGBTQ+ Films Coded and Explicit 1887 – 2025, which examines the representation of gay, lesbian, and trans people in film from the earliest silent films to the present. The movies are not porn, and his commentary is not superficial single-paragraph plot capsules, but comprise critical essays, some several pages long, about this vast history of films, both famous and unknown, looking at the imaging of queer people in international cinema. To this day Douglas continues to wake at midnight (he goes to sleep in the early evening) and begins viewing films online and researching and writing his essays. He pauses for lunch—our only meal of the day—which I prepare, then returns to his work. Like the admiring Random House exec, I envy Douglas’ creativity and drive. My husband is both a dreamer—which is what I love most about him—and a realist, who prodigiously gets things done, which I also love about him.

Except for our being queer, and for the life-infusing vitality of our careers, we’re probably one of the most heteronormative gay couples most folks are likely ever to meet. We’ve always been monogamous—except for that bounded period when I weekly slummed it at the gay movie houses, when we nevertheless remained steadfast in our true and exclusive relationship. We’ve always worked steadily. We never frequented the gay bars or participated in the “gay lifestyle.” While we knew and worked with many gay guys and some lesbians, most of our friends were straight. It was never boring or confining to us. We loved our life just as it was. It would not be inaccurate to brand us as assimilationists.

Douglas and I bicker and gripe with each other nearly every day, about this or that. One of us didn’t clean up his cookie crumbs; the other of us forgot to check the mail. Neither of us RSVP-ed to some invitation. And our attitude can get a little rankling, too. Whatever the declared matter might be almost doesn’t matter. Sometimes I think we bitch at each other almost for sport. Ten minutes later we might be discussing what to have for dinner: Should we have osso buco? Pizza? Lox and bagels? Thai carry-out? At heart, if we clear the air of all the relational pollution and smog in our household, we have a settled, happy, and fulfilling marriage. Fifty-five years of it, for better or for worse, in sickness and in health, to death do us part….

And thank you! I've gotten a lot of "likes" on this 4-part series, but few comments. I'm so pleased to found it a lovely story; it's also a love story.

Regards,

Howard

A lovely story. Thank you so much for sharing.