Bicycle Repair for Ladies and Revolutionaries

When cycling took over my life, it became an obsession that rivaled what I had once felt for other women.

Each week, The Queer Love Project publishes an original essay. Want to submit your essay and add to our growing archive? Find our submission guidelines and more here.

I have fallen in love as many times as I’ve fallen off a bicycle—too many to count on my fingers alone.

I fell after I crashed and skinned my knee at Camp Redwing—because I lost control cruising down a steep hill—and then slept off the embarrassment in a tent next to my crush. Bugs bit our elbows and palms until tiny constellations formed around my cuts and scrapes. By September, the wounds had healed and my crush had stopped returning my letters.

I fell while on family vacation and again on our hometown river trail because my bike followed my eyes, and I couldn’t keep my gaze off the friend at my side.

I fell riding on Coronado Island with my college girlfriend, the most athletic woman I have ever dated. I skidded in the sand going around a hairpin turn, and she was so far ahead on the road that it took her a full five minutes to come back. By winter, she had grown tired of how I slowed her down.

That was it. I had had enough falls. I swore off bicycles, a vow of chastity that would last for the next ten years.

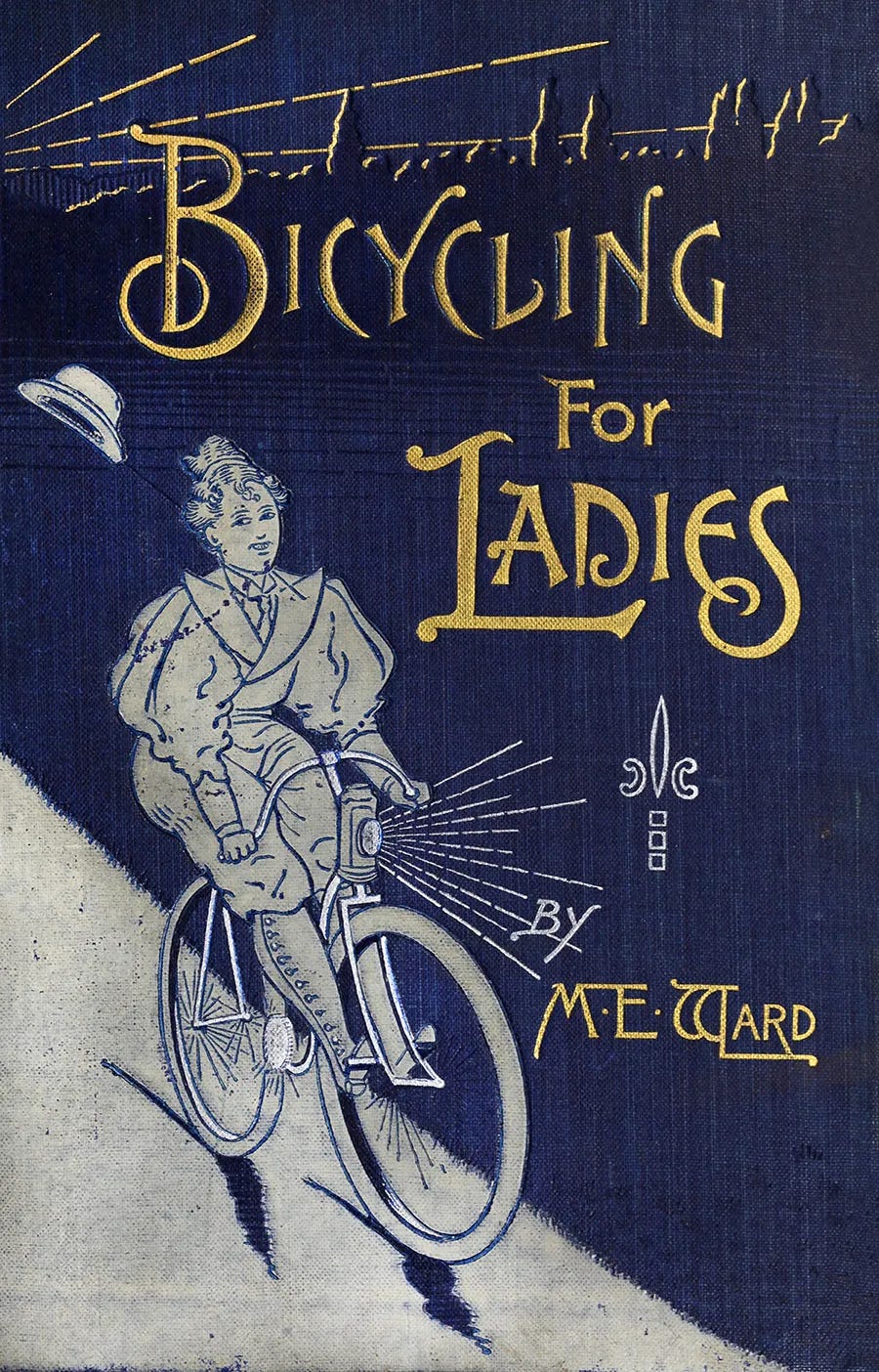

Where I found injury and instability in cycling, the queer women before me had found something more revolutionary in this human-powered mode of transportation. Maria “Violet” Ward’s instruction manual Bicycling for Ladies, with explanatory illustrations based on photographs by Alice Austen of the gymnast Daisy Elliot—a band of three little-known Victorian-era lesbians who lived and loved on Staten Island—is filled with mind-numbing suggestions for how best to mount a bicycle in a heavy skirt and maintenance instructions for a machine that has been modernized and improved upon thousands of times since the book was originally published in 1896.

“The drop frame is made to facilitate mounting and to permit the adjustment of a woman’s dress,” wrote Violet. “Wear an old dress, easy shoes and gloves, and a hat that will stay on under any condition.”

Somehow, though, through all how-to guidelines, the giddiness of these three women at the possibility all these mechanics provided shines through: “It supplies, too, a new pleasure—the pleasure of going where one wills, because one wills.”

Bicycling for Ladies came out the year Alice turned 30, an age when some of the other women in her social circle began to get married and have children. The year I turned 30, I finally returned to—and mastered—the art of riding a bicycle out of sheer necessity.

When the New York City subway system reduced its hours and advised only essential workers to ride the trains and buses to limit the spread of Covid-19, my world shrank. I didn’t have a car. I could hardly walk to the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, let alone all the way across it into Manhattan. It wasn’t until my new lesbian neighbors loaned me their old bicycle—a woman’s mountain bike, too short for any of us, with a sloped crossbar so that the rider might easily mount in a skirt if she so desired—that I was able to leave the orbit of my neighborhood and see the city where I had lived for eight years: Lady Liberty guarding the harbor; Coney Island, with the stalled rides of Luna Park looming over the cigarette-littered sand; the Brooklyn Museum, where thousands of people dressed in white gathered out front to protest the murder of Black trans people; the encampment at City Hall, just at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. My sudden independence connected me to a community.

Cycling took over my life. It became an obsession that rivaled what I had felt for other women in the past. I bought velcro sandals so they would not fall off while I peddled and a fanny pack to lighten my load while I rode. I only read books that would fit inside the small bag, poems and manifestos, like Dean Spade’s Mutual Aid, another how-to guide, one that treated the project of solidarity as if it were as easy to learn as riding a bicycle.

If I was truly honest, though, the entire project was laced with the kind of romance I had promised myself I would avoid. The lesbian neighbors who had loaned me their bike? I dreamed of joining their relationship. In the aftermath of my own breakup (again) and ensuing move to this new neighborhood, it was easier to fantasize about basking in the light of someone else’s love than to face the realities of building my own. I rode that bike to a date in Prospect Park in the middle of a tropical storm, and then to another all the way in East Harlem in sub-forty degree weather. Independence, I had found after nearly a year of lockdown—waking up alone on my birthday and Election Day and Thanksgiving, with a similar fate surely awaiting me on both Christmas and New Year’s—could get a bit lonesome.

Letters between the three creators of Bicycling for Ladies—writer Violet, photographer Alice, and model Daisy—reveal that they had other pastimes outside of cycling. The women’s entanglements with one another had begun long before they began work on the book together. Daisy and Violet were a romantic couple, though as the project wore on, the model’s affections began to turn from the writer to the photographer. In July 1895, likely already hard at work on the book project, Daisy wrote to Alice: “As I told Violet the other day; I love you, and should anything happen to her, you should be the first one I should turn to.” When it comes to narrative, their letters make for more interesting reading than a bicycle manual.

The year after the book came out, a few months before Daisy embarked on a summer bicycle trip across the Alps, she wrote Alice a Valentine that suggested her feelings for the photographer had eclipsed what she had felt for Violet. “You know that I love you darling; there are many things I think of that I would like to do for you, yet there is so little that I really can.” It seems that these feelings, though, like the letters, were one-sided. “I am beginning to be very home sick for a letter!” wrote Daisy. “It is a month since I saw you last and all I have had is the letter at Bremen.” Daisy’s dreams never did come true. That same year, Alice would meet the woman who would become her partner for over 50 years.

Now, even in an era when women can be more independent, riding a bicycle still provides a special freedom. I can’t put my finger on why until I stumble across a line in the little orange book that has been accompanying me on my rides. For Spade, transportation, whatever the mode, is one of five “means for getting by,” alongside “food, health, housing, [and] communication.” In our present system, he writes, all five are controlled by capitalism.

All the bicycles I rode that first year, though, were gifts. My boss gave me the old bicycle that had been her Zoom background through our many months of virtual meetings, the one that she rode before she married and gave birth to a daughter, quickly followed by twins. Then, my roommate flew home to her family in California and never returned. She left behind a rug, a ratty old couch, a chinoiserie salt cellar, and a 2019 Trek bicycle, barely ridden.

“I moved through partners as quickly as I moved through bicycles, too isolated to get much assistance with the repair.”

Violet encouraged readers and riders to find ways to share their “wheels,” as well as the responsibility of maintenance. “Buy two bicycles,” she wrote, “and form as small a club as can manage their purchase. Keep a register, and pass the bicycles from member to member, for say a week at a time, repairs in case of an accident to be paid for by the member using the wheel at the time of the accident.” Violet and Alice turned this vision into a reality as the co-founders of the Staten Island Bicycle Club, with a “wheelery” located at the Club’s headquarters, to provide “rentals and repairs,” and later with the Staten Island Bicycle Shop, which Violet managed. Their endeavors aren’t a far cry from Dean Spade’s vision, over a century later, of energy grids built on a foundation of mutual aid, “cultivated and cared for by the people using them.”

I moved through partners as quickly as I moved through bicycles, too isolated to get much assistance with the repair. An entry from the register on the latest accident: After a year-and-a-half-long courtship filled with longing voice notes, the digital descendants of Daisy’s unanswered letters, I dated my best friend. They wanted two nights a week, preferably at a bar, and I wanted someone to cook dinner with, to slot into my routine and make my junior one bedroom apartment feel a little less cavernous. Heart, a bit bruised. Hands, itching to pick up my phone and call.

I packed up the pieces and boarded a flight to Des Moines for a straight wedding. At the opening garden party, as the wives swapped tips about the best exercise equipment and the husbands celebrated how gentrification had improved their property values, I could almost see why my ex had refused to be my plus one. I rode the chartered buses to the official wedding events and took an Uber to the Iowa State Fair, but I always peered out the windows at rusted bicycles locked to No Parking signs along the route. My feet itched to pedal the land.

The hotel concierge directed me to the Bicycle Collective, where residents can receive free instruction on how to repair their own rides. Twenty minutes later, I walked into a shop that looked conjured straight from the pages Bicycling for Ladies. A spry man greeted me at the front and gave me a tour of the hundreds of bicycles cluttering the space, waiting to be refurbished and sold to fund the lessons. The sight also reminded me of New York City’s abandoned bicycles, attached to bus stops and street signs, chains rusted and seats missing, yet still salvageable, if only I knew how. Bikes stored in my building’s basement, tires gone so flat with disuse that they almost look square. “We live in a society based on disposability,” writes Spade. The book has been left back at home, but the words echo in my mind. What use is holding on to a bicycle if it’s not being ridden?

This trio that captured my heart was not alone in their embrace of cycling as a means of independence. The Wheel was the emblem of the New Women, and its enthusiasts included the novelist Willa Cather; Susan B. Anthony, who famously said, “I think [bicycling] has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world,” and her compatriots in the suffrage movement; and late blooming rider Frances Willard, who fondly referred to her bicycle as “Gladys.”

The kind man at the bicycle collective could not rent me a bicycle because the shop didn’t have the right insurance. For that, I headed out of town to Kyle’s bicycles, where two men fudged the rules to rent me the nicest Wheel I have ever ridden: a red carbon number worth three grand. They lent me a helmet, promised to keep the shop open for as long as I needed, and dangled the possibility of a beer when I returned to keep me motivated through the twenty-mile solo ride I had planned.

“I had been too focused in my pursuit of a partner, one that would last, to notice it before. Our independence is inextricably linked to our interdependence.”

I biked across the flat land with Violet’s words cheering me on: “A bright, sunny morning, fresh and cool; good roads and a dry atmosphere; a beautiful country before you, all your own to see and enjoy; a properly adjusted wheel awaiting you—what more delightful than to mount and speed away, the whirr of the wheels, the soft grit of the tire, an occasional chain-clank the only sounds added to the chorus of the morning, as, the pace attainted, the road stretches away before you!”

Out in the quiet of the corn fields, names bubbled up in time to the cadence of my feet, their easy circles that propelled me forward. My lesbian neighbors. My old boss and my old roommate. The two men at Kyle’s, neither of them named Kyle. My exes, none of them still in my life but all still a part of the wider community that brought me here. Daisy and Violet and Alice. Perhaps it was the heat and the famously humid “corn sweats,” but suddenly I felt like I could see it. (Is this what links cycling to revolution? It’s impossible to write about either without sounding corny.) I had been too focused in my pursuit of a partner, one that would last, to notice it before. Our independence is inextricably linked to our interdependence. Our histories, personal and collective, can contain clues to our future liberation.