Gray Hanky, Left Pocket

Historian and scholar Allan Bérubé taught me how to say a lot without a single word.

Each week, The Queer Love Project publishes an original essay. Want to submit your essay and add to our growing archive? Find our submission guidelines and more here.

This essay is adapted from a memoir-in-progress titled Dance While the Record Spins.

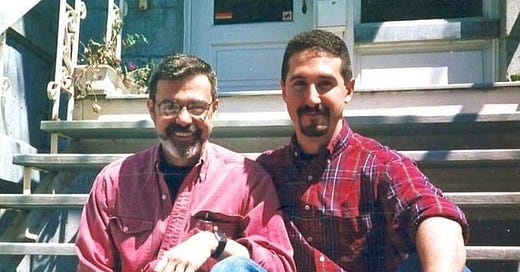

The first time I saw Allan Bérubé was in 1990. He was speaking at a lesbian and gay student conference at Harvard. I had come to hear him with some of my fellow queer activist undergrads from just up the road at Tufts. His award-winning book Coming Out Under Fire—still the authoritative history of gay men and women in the military during World War II—had just been published. I remember thinking he was a good speaker, smart, with loads of charisma. I remember thinking he was sexy, with his innocent chipmunk smile and his devilish eyes. But most of all, I remember what he wore that day: black jeans and a dark flannel shirt, with thin leather suspenders hooked to his belt-loops and a gray hanky peeking out of his back left pocket.

He was flagging. As a bondage top. At an academic conference. At Harvard. But he was doing it as subtly as possible, so subtly that most people in the room—too young to know the 1970s hanky code—never noticed.

Despite my age, I knew the hanky code, and believe me, I noticed.

Seeing Allan speak, I realized: That’s the kind of gay man I want to become. Someone who gets to speak at prestigious institutions but isn’t overly impressed by them. A gay man who operates with a keen sense of self-awareness and pride, who isn’t cowed into hiding who he is—ever, anywhere. Someone who can speak multiple languages at once: one with his words, another with his clothes.

I was smitten. By his brains, his salt-and-pepper beard, his sheer chutzpah. I was 19.

The second time I saw Allan was five years later, in early 1995, when he spoke about the history of gay bathhouses at the LGBT Community Center in New York. He had recently moved to the city from San Francisco after getting a Rockefeller grant to do research, and he gave the opening speech at an extremely contentious town meeting about the burgeoning crackdown on gay sex spaces in New York. Hundreds of activists on all sides were screaming, yelling, name-calling, but Allan remained completely calm, ever the level-headed historian.

As part of the Dangerous Bedfellows, a group of queer grad students from NYU, I was putting together a book about the crackdown called Policing Public Sex, and I approached Allan after the meeting to see if we could publish his speech in the book. He said yes. And then he asked me out. I said yes. I was 24. He was 48.

Our age difference wasn’t fodder for any kink; he was not my daddy and I was never anybody’s boy. Yet the generation gap did provide a lot of what might be called “cultural exchange.” I got him listening to 1990s alt-rock bands like Oasis and Everything But the Girl, and reading David Sedaris. He told me stories from the 1970s: how he dropped out of the University of Chicago to protest the Vietnam War, and later joined a weavers’ commune in Haight Ashbury. And he told me stories from the 1980s: in particular, the early years of AIDS, which had claimed his most serious lover, Brian.

We were together two-and-a-half years, and we had exactly one fight. I had met Eric Rofes—another gay historian from San Francisco—at a conference, and we’d become friends. Allan, who’d known Eric for many years, was aware of this and had no issue with it. But when it became apparent that Eric and I were also having sex (at that conference, or on his visits to New York), Allan grew uncharacteristically jealous.

We had an open relationship, so the sex itself wasn’t the issue—jealousy was not something we typically had to wrestle with—but this time it struck a nerve. Perhaps because Allan viewed Eric as a rival professionally—something I hadn’t previously appreciated. Allan asked me to stop sleeping with Eric, and I conceded without an argument. (Even open relationships have boundaries, and even people who are intellectually fine with non-monogamy are allowed to have feelings.) Eric was disappointed in me, asking why I caved in so quickly if I valued my sexual independence.

“He’s only ever asked one thing of me,” I told Eric, “so it must be very important to him.”

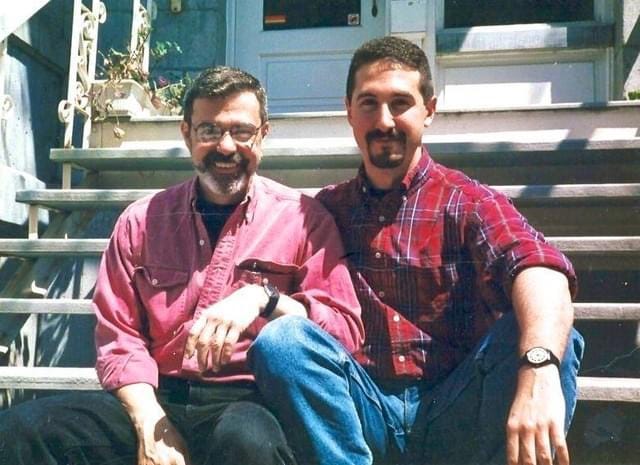

The details I remember most clearly about my years with Allan are the most seemingly mundane: nights on my couch watching The Simpsons (another 1990s thing I introduced him to), nights on his couch watching Bugs Bunny (so he could point out all the coded gay language in many episodes), or the night we spent on a friend’s couch watching the coming out episode of Ellen. We’d rent a film noir, walk on the piers, maybe go to a leather bar. Our dinners out were never fancy: Chinese food or a diner, always Dutch treat. (He was also never my sugar daddy.)

Our birthdays were just a few days apart, so we shared a couple of birthday parties; his 50th, for instance, was also my 26th. We took one big trip—to Montreal, where he reveled in his Quebecois heritage—but for the most part, we stayed in Greenwich Village, where we both lived, a 10-minute walk apart. A large percentage of our dates involved giving each other articles and books to read, critiquing each other’s writing, and going to activist meetings and protests around the city. That kind of thing turned us both on.

Allan was known for his slide shows, in an age before PowerPoint. In the 1970s in San Francisco, he gave a presentation about women who passed as men—and married other women. He later toured with a slide show called “Resorts for Sex Perverts.” By the time he and I were together, he was giving a slide show about queer, cross-racial, working-class organizing in the 1930s and ’40s in the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union. His work was sexy, always outside the bounds of the “good gays.” But it was solid work.

I got some unique insight into his research when he hired me to transcribe hours and hours of oral histories he’d done about the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union. He was in the process of expanding his slide show into another full-length book—sadly, one that remains unfinished.

I remember the first time he met my parents. I had worried it might be awkward, as it often is when you introduce them to a boyfriend. But they hit it off right away. Allan and my mother were only a few years apart, and they had similar backgrounds; she grew up as the poor child of immigrants, in working-class Jersey City, while he spent much of his childhood in the Sunset Trailer Park in nearby Bayonne—something he wrote about in an essay that he co-authored with his stepmother Florence.

I was visiting my parents in Maryland in 1996 when Allan called to say he’d won a MacArthur “genius grant.” I kvelled. They kvelled.

That money allowed Allan to stay in New York City to continue his research. It also allowed him to move out of the room he’d rented on Jane Street—in the basement of the brownstone owned by yet another gay historian, Jonathan Ned Katz—and buy his own apartment in Chelsea with a view of the Empire State Building.

That’s about the time we broke up, in early summer 1997. There was no fight, per se; I had fallen in love with Allan, and he was realizing that the feelings would never be fully reciprocated. For whatever reason, he said—perhaps because he’d lost his lover Brian to AIDS several years earlier—he wasn’t capable of offering the kind of romantic attachment I was looking for.

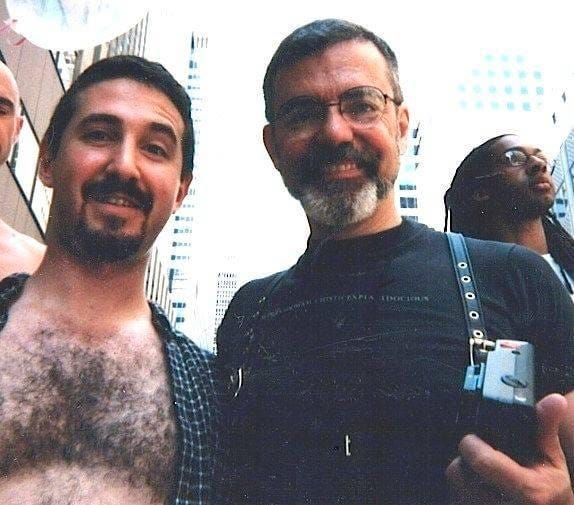

The break-up wasn’t the end of our connection. Shortly after I took a quick trip to San Francisco that summer—where I cried to Eric over being dumped—Allan and I took a road trip with the Dangerous Bedfellows. (The anthology we co-edited, Policing Public Sex, had come out the previous year, and included Allan’s history of gay bathhouses.) Our destination: Provincetown.

I never made a mixtape just for Allan, as I’d done for previous boyfriends; he seemed like the wrong generation to appreciate that kind of thing. But I did make a mixtape for that drive to Provincetown in 1997, for Allan and the Dangerous Bedfellows. Since it was for the whole group, I picked a few songs that each person in the car might particularly appreciate—which resulted in a mix of easy listening, disco, house, and FM radio throwbacks. I ended the tape with “Wonderwall” by Oasis, which I chose specifically for Allan, because I always thought of him when I heard the line: “I don’t believe that anybody feels the way I do about you now.”

I have returned to Provincetown every summer since that 1997 trip, and the mixtape became something of a tradition: Every subsequent summer, I’d make a tape that reflected the people in the car that year. That always included my friend Ephen—one of the Bedfellows—and also included Allan for a couple more years, until he moved on to other boyfriends and other vacations. Even after he stopped joining me in Provincetown, however, my post-breakup friendship with Allan would endure many more years, and lead us to places we had never been. In the end, it led us both, unexpectedly, to the Catskills, which is where we were both living, a 10-minute drive apart, when he died in 2007.

I still have the teddy bear Allan gave me when we were together: Bayonne, named after his hometown. I also have the mixtape he bought for me in 1998, on our second trip to Provincetown; he wasn’t interested in making tapes himself, but he knew how much I valued them. This one was a collection of the summer’s most popular songs from tea dance at the Boatslip, where we’d gone dancing many afternoons in Provincetown, put together by the club’s resident DJ Maryalice. The highlight was Stars on 54’s effervescent cover of Gordon Lightfoot’s “If You Could Read My Mind,” which still reminds me of Allan every time I hear it. (It also reminds me of our generation gap: I was in my twenties when the cover came out, while he was in his twenties when the original came out in 1970—the month I was born.)

But the most important thing Allan gave me was the sense of pride that I noticed when I first saw him speak at Harvard: fearless without (always) being strident. Sometimes, when I’m speaking in public now, I like to pay tribute to him by wearing a (light blue) hanky in my right back pocket, knowing that there might be one person in the room who’ll notice, and understand.

Verklempte over here. Thank you, Wayne, for bearing witness to this legacy.

reading this essay was such fortuitous timing - im reading Bérubé’s work right now about the MCSU!! i just watched his slideshow on outhistory.org - his work is so inspiring for a little queer archivist like me, and im grateful to learn more about him from his loved ones!!! ❤️